When you deal with problems in life, you develop a variety of coping mechanisms. Some of them are healthy while others can cause you additional issues. Everyone has the occasional negative thought.

However, when those negative thoughts become the norm, it can lead to a cognitive distortion.

There are several forms of cognitive distortions. Therapists utilize cognitive behavior therapy to help retrain their clients minds and teach them to adjust their thinking. One form of cognitive distortion that cognitive behavior therapy can treat is fortune telling. Before we look specifically at fortune telling, let’s define cognitive distortions a little better.

What Is A Cognitive Distortion?

Cognitive distortions are negative thought patterns that give you a skewed perception of reality. These are coping mechanisms that people develop when they face hard times in life. The more severe or lengthy the time of hardship, the greater the chance of developing cognitive distortions.

When negative thoughts become a habitual way of coping with adverse situations, you start to believe things that aren’t factual. Your mind adapts to this negative thought pattern. This is the essence of a cognitive distortion. One such cognitive distortion is fortune telling.

What Is Fortune Telling?

When you think of fortune telling, you may think of the lady at the fair who is peering into a crystal ball. While that is a fun-and-games scenario of looking into the future, the cognitive distortion by the same name is quite serious. In this way of thinking, you are convinced that you know what will happen without having all of the information.

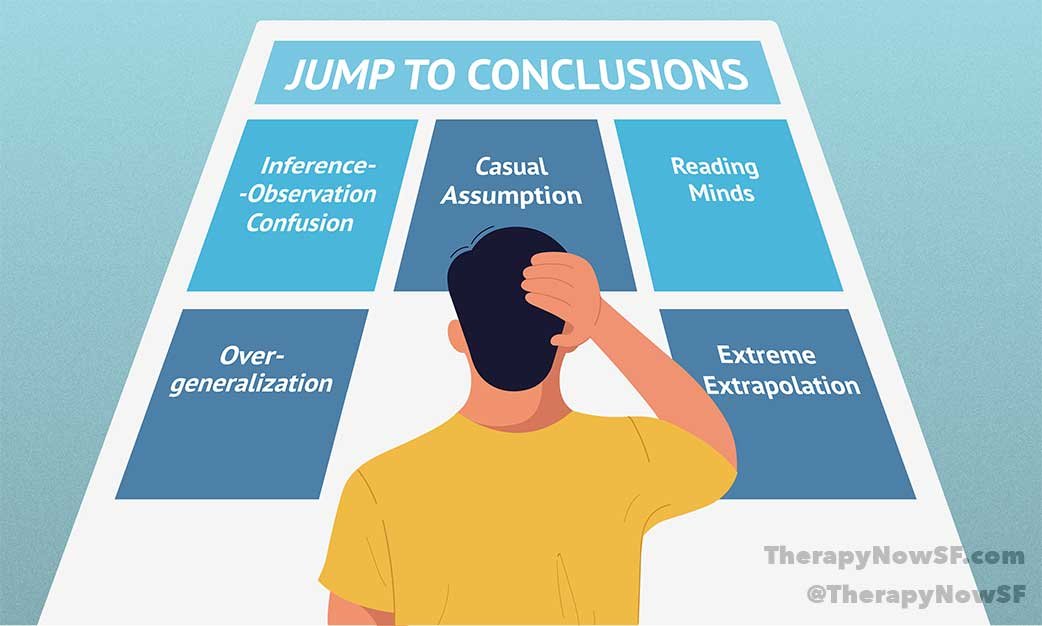

Everyone experiences a bout of fortune telling behavior on occasion. It’s easy to jump to a conclusion on a bad day. It becomes a problem when every scenario has a negative outcome in your head, and you haven’t taken the time to gather all of the facts.

Fortune telling behavior happens more often when someone is anxious or depressed. Those disorders keep you feeling on edge. Feeling nervous or extremely sad allows negative thoughts about yourself or your situation to enter your mind. You begin to predict what will happen and can’t be convinced that you are incorrect.

Fortune telling behavior can affect the relationships you have with others. If even one thing is different than what you expect, you can begin to tell yourself that the friendship won’t last. You will begin to make choices based on what you think will happen instead of based on actual events.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

One way to help adjust the negative thinking that causes fortune telling is cognitive behavior therapy. This type of therapy helps you not only recognize the harmful thoughts but also to begin having more healthy thought patterns. This therapy doesn’t have instantaneous results. It’s goals-driven and tends to take a specified time frame.

Final Thoughts

Fortune telling predicts the future based on faulty thinking. Everyone can exhibit this behavior at times, but it becomes a problem when it’s a constant pattern. Cognitive behavior therapy can be beneficial in changing these thought patterns.